How Breweth Java With Jesus

Posted: 2005/11/08 by sun in[from The New York Times, October 23, 2005]

How Breweth Java With Jesus

By DAMIEN CAVE

STARBUCKS coffee cups will soon be emblazoned with a religious quotation from Rick Warren, the best-selling author and pastor, which includes the line, "You were made by God and for God, and until you understand that, life will never make sense."

Meanwhile, hipster havens like Urban Outfitters have made a mint selling T-shirts declaring "Jesus Is My Homeboy." Alaska Airlines distributes cards quoting Bible verses, and at least 100 cities now have phone directories for Christian businesses.

Clearly, business owners have sensed a market opportunity. The question is whether it's a mutually beneficial relationship.

"The way in which religion allows itself to be reshaped by the larger culture, including markets, allows it to prosper and do well, but it also clearly changes its core values," said Charles Ess, a professor of religion at Drury University in Springfield, Mo. "The oldest Christians sold all their goods and shared them in common. They didn't shop and launch marketing campaigns."

Then again, Christianity seems to have done quite well by mixing worship and commerce. "Religion is like yeast in dough," said Michael Novak, a theologian at the American Enterprise Institute. "It's in every part of life, so for it to show up everywhere is only natural - in commerce, politics, sports, labor unions and so on and so forth."

Not that the intermingling of faith and commerce is anything new. Christians have always used all available means and venues to spread the gospel.

"Jesus taught in the temple and the marketplace," Mr. Warren, the author of the blockbuster "The Purpose Driven Life," said in an interview.

When those with political power signed on, the intermingling of faith and commerce became official. The Roman emperor Constantine I may have started it all by converting to Christianity in the early fourth century. His epiphany led to the official sanctioning of the religion, transforming Christians from a persecuted minority to an honored elite. Overt expression of faith became a tool for getting ahead.

"If the empire is Christian and you're seeking power or success, well, you join the church," Professor Ess said. "Once it becomes a mainstream tradition, people join for all kinds of reasons."

"Since that time," he added, "the Christian church has been fairly savvy about the mix of power and faith."

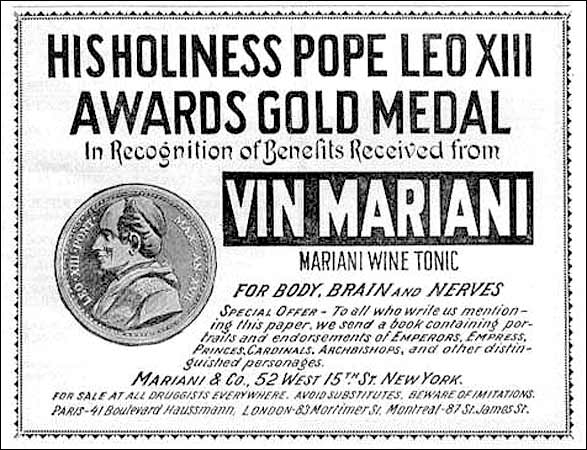

Western history is rich with examples of the church-commerce concoction. In the 1800's, the image of Pope Leo XIII appeared on posters for Vin Mariani, a wine with cocaine that was a precursor to Coca-Cola. The pope honored the drink with a medal to show his appreciation for its effervescence.

In the England of the Industrial Revolution, Methodism and Wedgwood pottery spread from the same kiln. John Wesley and Josiah Wedgwood were friends and fellow Christians who joined forces in what might be described as cross-platform marketing.

"Wedgwood built its global pottery industry by selling little statuettes of John Wesley and the other superstar preachers of the day," said Philip Jenkins author of "The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity." "British capitalism was built on religious marketing - well, maybe."

In the early days of the United States, businesses, for the most part, did not use religion to sell products. They lacked the technology for mass production, and the Puritan influence helped forge an opposition to showiness or material embellishment.

And according to Robert W. Fogel, a Nobel-winning economist at the University of Chicago, the public largely assumed that prominent businessmen were devout. Many were educated in universities that focused on theology. Their products did not reflect their beliefs because their lives did.

"John D. Rockefeller is a classic example," said Mr. Fogel, author of "The Fourth Great Awakening and the Future of Egalitarianism." "All of his life, he gave 10 percent of his income to the Baptist Church."

From World War I to the 1950's, the nation became more secular, Mr. Fogel said, while the business of advertising and mass production rose. The advertisers sought to woo everyone, regardless of creed, and so avoided Christian themes.

In parts of the country, however, there was still a feeling that a business owner ought to be a devout Christian, and those who were not, like Jewish executives in Hollywood, often felt pressure to make a public show of addressing that expectation.

"That's why films in the 1940's show all Catholic priests as supermen," Mr. Jenkins said. "That may be the best example of intimidation, which of course only works when the assumption is that some businessmen are not good Christians. The more people assume that business is secular humanist liberal - e.g., by giving gay partner benefits - the more they may feel a need to reconcile 'people of faith.' "

And that may be position of Starbucks. It was widely criticized by evangelical Christian groups last summer after its cups included a quote from the writer Armistead Maupin that said, "My only regret about being gay is that I repressed it for so long."

Robert H. Knight, director of the Culture and Family Institute, one of the conservative groups that led the charge, said the company's support for liberal causes made it an obvious target.

"Starbucks has long served up a New Age secular worldview," he said. "It's about time that they acknowledged that 90 percent of Americans believe in God and that millions of them are Christian."

Starbucks executives deny that the company was trying to placate religious groups when it decided to add Mr. Warren's quote to its cups. "We're trying to show a diversity of thought and opinion," said Anne Saunders, a senior vice president in charge of marketing. "There is not a quote that's an answer to another."

In any case, if religion is good for Starbucks, is Starbucks good for religion? Being associated with a $5 soy mocha latte may spread the word, but at what cost to the image of a heartfelt faith?

"Sometimes it's so vulgar that it's not particularly good for religion," Mr. Novak said. "But if religion is in everything, it has to be in the vulgar stuff, too."

-------------------------------

In the 1800's, Pope Leo XIII's image was found on posters endorsing Vin Mariani, a sparkling red wine made with cocaine. Particularly fond of the drink's effervescence, he honored the wine with a gold medal.